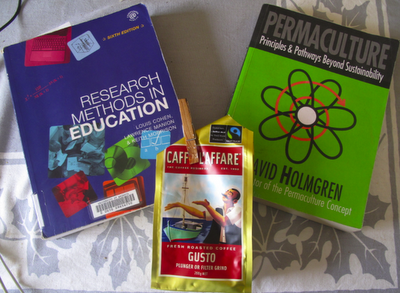

We have an addiction to P in our home. (Note: In no way do I mean to diminish the real problem of P addiction in NZ – indeed, in our neighborhood – or in the USA known as “meth.”) The P addiction in our home is all about permaculture. Please be aware that permaculture is not the only ecological design system that exists on this glorious planet, but some say that it is the most comprehensive. To that, I add the most documented. Permaculture has over 30 years of books, magazines, and even a few peer-reviewed papers, as its chronicle. This is particularly useful for those (ie, me) writing doctoral theses on ecological design in science education.

The P addiction in our home results from an approach to permaculture not as a set of principles to memorize and apply in a formulaic manner, but rather as a way of seeing the world. In other words, permaculture as systemic, not systematic. This perspective, for me, results from decades-long involvement in ecological design and a learning disability that was misdiagnosed (ignored) in my youth. In other words it is a combination of nature and nurture. I was born with a brain that is better at seeing at the space in between things than the things themselves. While this may have contributed to my success as an All-American lacrosse attackman (ie finding my way between large defensemen), it also inspired my second grade teacher to alert my parents that I would never read. Luckily, they were both teachers themselves, and sent me to a tutor instead of to the meat works (to work, that is, not to contribute my flesh).

Ethical note: NOT my second grade class. This looks like 4th grade. Wait, maybe 6th grade.

Regarding nuture, I’m not referring to the 17 years of private school or to the amazing support given to me and my brother by our parents. If anything, the rigid, traditional schooling I experienced for much of my life suppressed my potential for systems thinking. The main lesson I learned from school is that it was all a game, and the playing field was tilted in favor of certain brains and away from others. My brain was an other, and I struggled mightily not to drown (below C-level) through primary school, middle school and into high school. Around the time I hit my stride in lacrosse, I also figured out how to play school. Interestingly, some psychologists suggest that certain people outgrow their ADD after going through puberty. I don’t know if that was the case for me because I’m definitely still ADD. Instead, I think that I figured out how to succeed in a reductionist paradigm by taking a systems approach. Although I considered earning good grades a game, I never took it as seriously as lacrosse because I did not respect it. It was more of a joke, where sport is serious business.

It was not until I had graduated from university (Magna Cum Laude, now that is a joke) until I came to the unfortunate realization that I hadn’t learned how to do anything in all those years at school. I could not grow a garden. I could not prune a tree. I could not build a house. Seventeen years of private education and all I got is this lousy scroll! No, the nurturing of a more holistic perspective did not occur until I began learning how to grow food, prune trees and build – ok, renovate – houses. A garden, a tree and a house are not things. They are systems, and we can never hope to understand them from a reductionist perspective. And for me, luckily, the seed I was born with was not terminated by a “Round-Up Ready” education. I’ve heard that certain seeds can remain viable for decades and even centuries. By those standards, 17 years appears fair to middling.

But I reckon that was good enough because it germinated in the humus of a pumpkin patch and the dust beneath a crosscut saw. And during the ensuing 17 years (and then some) I’ve nurtured a holistic perspective by actively practicing systems thinking. It was not easy at first, but with practice strides came. As I took up running marathons I made the easy connection between exercising my body and exercising my mind. At the same time, as a professional science teacher (go figure) I began to develop systemic pedagogies. In other words, teaching ecology in ecological ways. The release of creativity inspired me as a teacher and inspired many of my students. (Some still preferred reductionist approaches to teaching and learning. Most likely because they were familiar to them, and that they had found numerical and alphabetic success under them.)

And around that time I found a Masters program developed and delivered by the amazing Coleen O’Connell and Cloe Chun. Mind you, I had no intention of ever going back to school as a student. But they were willing to embrace a different paradigm for education that resonated with me. I can vividly recall Coleen selling the Masters in Ecological Teaching and Learning to me at the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests building in Concord. I listened politely and told her, “I do all those things already.” She replied, “And you should get credit for them.” I was sold, especially because my employer paid for the degree.

I really must thank Coleen and Cloe for helping advance my education practice, which has lead me here to this computer in this foreign land and an email address that ends in ac.nz. And I must thank the New Zealand government for offering affordable tuition to international doctoral students and very reasonable health coverage. And most of all I must thank my supervisors Chris, Kathrin and Richard. But especially Chris for being an awesome colleague and friend.

Centre for Science and Technology Education Research community garden great potato harvest of 2011.

To his credit (and maybe his regret) he encouraged me to do my research “in a permaculture way.” This half-sentence of advice has made the process of PhD research more dynamic, more enjoyable, and hopefully more robust. For example, the methodology chapter in most theses is direct, dry and formulaic. In other words, dull to read and boring to write. Thanks in part to Chris’ advice, a holistic permaculture perspective, and drugs (not P), I have had a lot of fun writing this chapter.

Three a day keeps distraction away.

I have engaged with the material and, in my opinion, created something entirely original. Many synergies exist between permaculture and education research. It is just a matter of creating a guild.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Oh, that was exhausting. For you too? This post takes a different approach than previous posts. If this is your first read, take some time to explore others. There should be something here for everyone. Maybe not Rick Perry.

For a snippet of the methodology chapter, see below. Please note it is an unedited first draft that I wrote this morning on 3 pots of organic fair trade coffee. I’d appreciate any insights or feedback. I may even acknowledge you in my thesis.

Peace, Estwing

The P of METHedology

4.7 Validity and Reliability

Many tables have four legs, but stability requires just three. A guild of three complimentary plants – such as the Hopi “Three Sisters”: corn, beans and squash – provides a stable cultivated ecology for growing food. A ship lost at sea can find its way using three beacons by a process called triangulation. In research, triangulation allows for stable (robust) findings and locates conclusions out of an ocean of data. Stable research is said to be reliable (Cohen et al., 2007).

But triangulation in every case described above is not a linear progression. In other words, two plus one does not represent the same incremental increase as one plus one. For example, a table with one leg benefits little from adding one more leg, but hugely from adding a third. Corn and squash planted together do not thrive like they do when beans are added to fix nitrogen in the soil to feed them. And a lost ship is still lost with only two points for reference. In all of these cases, there is a tipping point of integrity reached by triads when symbiosis turns to synergy. The whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts, and the system punches above its weight. Three, it appears, really is a magic number (Johnson, Year?)

In the world of research, triangulation is defined as the use of two or more data collection methods (Cohen et al., 2007). Campbell and Fiske (1959) contend that triangulation is a mighty way to demonstrate concurrent validity, and the process is deemed more or less essential for those doing qualitative research. Mixed method, or multi-method, approaches in social science research provide a number of advantages. For instance, blah blah…more here…

While major advances in validity and reliability occur between one and two, and two and three forms of data, subsequent improvements tail off quickly thereafter. A more-the-merrier attitude turns to four’s-a-crowd. That said, redundancy is bad neither in research nor permaculture. If one plant in a guild succumbs to an insect pest or disease, or if one method is found to lack validity, then an extra component in the system suddenly proves helpful. In fact, ecological validity in education research requires the consideration of as many characteristics and factors involved in the subject of study (Cohen et al., 2007). Brock-Utne (1996) promotes ecological validity when studying the adoption of new educational policies in actual classrooms. I submit that, when politics and scale are removed, that is essentially what I did in this case. In other words, I developed a new approach to teaching science, provided it to a teacher, and then attempted to chart what actually happened in his classroom. However, ecological validity can run up against boundaries determined by ethical considerations such as anonymity and non-traceability (Cohen, et al. 2007). These considerations were paramount for this study, which took place in a small school in a small town in a small country.

To be continued…

and continued…

and continued…

Local writer Helen Frances has penned a fabulous article for New Zealand Lifestyle Block that runs a full eight pages, profiling the couple’s unique philosophy and international perspective. Find one in the shops before the end of the month.

Local writer Helen Frances has penned a fabulous article for New Zealand Lifestyle Block that runs a full eight pages, profiling the couple’s unique philosophy and international perspective. Find one in the shops before the end of the month.